This is the text of the keynote presentation I gave at the University of Leeds Business School Festival of Ideas on 28th February 2018.

Introduction

Thank you for all making the journey to be here today, battling the snow and the ceaseless Siberian wind – “The Beast from the East”. Many of us working on the cities agenda are at this time also feeling buffeted by the winds of economic and technological change, which are causing huge disruption, and creating huge risks as well as new possibilities for our cities.

In this talk I will try to answer the question of what are the main trends and drivers for change affecting our cities in the UK, particularly our Core Cities (our second tier cities), recognising London has a different position amongst cities in the world?

I will talk about what does this mean for the ‘Smart Cities’ agenda in a city such as Leeds

I will argue that:

a) We need a new definition of ‘Smart Cities’ which puts people, human capital and governance at its heart; and

b) We need to move away from a focus on the ‘what?’ of Smart Cities to the ‘why?’ and in particular. I will argue that in the past, the; what’ has generally been firms and people in the digital sector installing clever digital hardware. But in the future, it needs to be about how of: all of us shaping our cities need to embrace the digital and data agenda – a principle of; digital by default’ and how we need to focus on the economic and social outcomes that can be driven by technology and change.

I will talk about the drivers of change affecting cities such as Leeds today, and what I think we need to do to respond to them. But I will start by going back 140 years in the history of Leeds. Because the fact is that our cities have always been adapting, growing and innovating in the face of disruption.

The Leeds Innovation District – creating a 21st century science park in Leeds City Centre

The City of the Past

It is 1888 and a young man from France who had moved to Leeds created the world’s first moving image, filming traffic on Leeds Bridge. Louis Le Prince had moved to Leeds because of the city’s capabilities in engineering-he joined the firm Whitely Partners of Hunslet, manufacturers of values and computers – and in – what would be today called the “creative industries” – the Leeds Technical School of Art had been founded in 1871.

It was a time of great innovation and change. Four years earlier a Polish refugee opened a stall in Kirkgate Market in Leeds, and in 1894 he went into partnership with a cashier from local wholesale company. Their names were Michael Marks and Thomas Spencer, and their slogan was “don’t ask the price; it’s a penny”.

In the three previous decades a new railway station, Leeds Central, was opened joined by the LNWR and North-Eastern Railway, which would go on to become the busiest transport hub in the north of England.

Some of the world’s most prestigious and productive workspaces had been created, such as Temple Works, Tower works and Alf Cook’s Print Works, setting new standards in workplace and production design and technology, and the productivity and welfare of the workforce.

In 1874 the Yorkshire College of Science opened with the support of local industry, teaching experimental physics, mathematics, geology, chemistry, biology, textiles and engineering and in 1887 (a year before Le Prince’s breakthrough) the college merged with counterparts in Manchester and Liverpool to form the Victoria University, before gaining its royal charter as the University of Leeds in 1904.

Clothworkers Court was the first building of the Yorkshire College of Science (photo taken the day of my lecture, which was in the University of Leeds Great Hall in this building).

The Leeds General Infirmary, which had been established in 1771 moved to its current site on Great George Street. The magnificent building was designed by George Gilbert Scott, who was advised by a nurse and social reformer called Florence Nightingale.

And in 1858 the new Leeds Town Hall was opened by Queen Victoria. It was the largest crowd to gather on the streets of Leeds, a record that stood for another 158 years until in 2015 an even larger crowd watched, at the same location, the start of the world’s largest annual sporting event, the Tour De France. The building of the Town Hall symbolised the rise in importance of the Leeds Corporation, building on its powers granted to it in the 1942 Leeds Improvement Act to regulate and invest in streets, lighting, sewerage, building regulations and street cleaning.

So why is this relevant to the issues our city faces today? Think about the issues and trends at the time: rapid technological change, innovation and interconnected industries, new communications systems, the role of education and colleges and universities, businesses investing in skills and in premises to boost their productivity; a city that was open to talent, to innovators and entrepreneurs from across the world; a focus on the health and well-being of the population; investment in infrastructure; and new forms of government and city leadership.

The City of Today – Drivers for Change

I believe there are seven main trends and drivers for change having cities such as Leeds today: rapid economic change; the growing importance of human capital – a skilled workforce; the trend of agglomeration (supported by connectivity); huge technological disruption; environmental shocks which make resilience a major issue; health and well-being; all of which have implications for city governance.

Economy

We are seeing the emergence of new sectors. Leeds made the transition from a predominantly manufacturing economy (although manufacturing remains a significant employer) to one where financial and services drove economic growth in the 1990s and the 2000s. But the city’s economy is changing again. Following a period of rapid private sector jobs growth between 2010-15 (including the fastest amongst any UK city 2014-15) in 2015-16, the last year for which statistics are available, there was a small decrease in private sector jobs in the city. If you get beneath the surface of the statistics for that year, there are some interesting dynamics. Manufacturing employment, in line with long-run trends, continued to fall. But there were also falls in employment in financial and professional services, the drivers of growth in the Leeds economy in recent decades. there was rapid growth in sectors such as digital, low carbon, medical devices, and the creative industries. The emergence of the creative and digital sector in our cities – what Doug McCwilliams has called the “Flat White Economy” has been phenomenal.

The geography of innovation is changing. Knowledge intensive jobs are coming back into our city centres. Many people predicted that technology would result in the death of cities; we would stay at home and work remotely. But as the economy has become more specialised and knowledge based, firms want to be located in city centres where there are high densities of face-to-face contact between people and knowledge producing firms and institutions (such as universities, hospitals and government). They want to be where skilled people can collaborate, compare and compete in close proximity to each other. As Bruce Katz has said, people are no longer driving to out-of-town office and science parks where they do research and development and keep their ideas secret within their buildings. They are coming into city centres (increasingly using public transport or walking and cycling) where they are sharing their ideas in the hyper-caffienated spaced between the buildings. These densities of activity are supported by rail and public transport networks which enable firms to access a skilled workforce across a wide area.

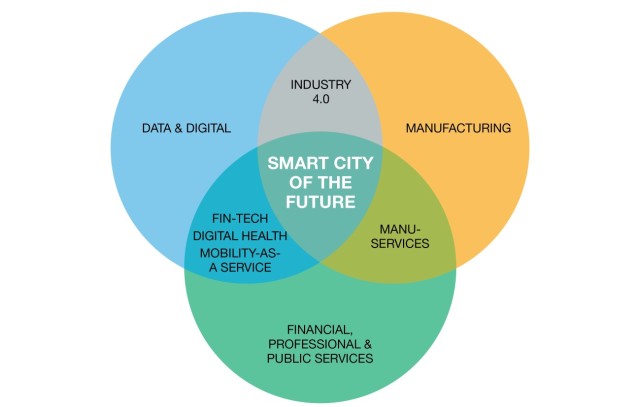

We are seeing the increasing importance of interconnected industries. Increasingly, successful cities are ones with diverse economies. Economic diversity builds resilience. In an era of great uncertainty it pays not to have all your economic eggs in a single basket. and as the boundaries between sectors become more blurred, it where different economic activities come together we are seeing innovation and growth, for example in Fintech, Manuservices, and Industry 4.0.

Interconnected Industries – it is where sectors come together is where we are seeing new high-growth economic activities emerge (diagram by Tom Bridges)

We also now have the productivity puzzle. Whilst job creation has been strong in Leeds, and in other major UK cities, in recent years. Productivity has flat-lined since the recession of 2008. There are many theories on why this is. The finger of blame has been pointed at: insufficient investment in R&D; poor education outcomes and a broken skills system; a failure to scale-up enough fast growth firms; the long-tail of small firms that are not productive enough; British managers – who like some British drivers – are not as good as they think they are; a failure to measure the modern economy accurately; poor infrastructure and sites and premisses. My own view, for what it is worth, is that the problem is not any one of these things; it is a combination of all of them.

We are also seeing a new urban divide. A divide between the successful global cities and everywhere else, between resurgent Core Cities – the main regional hubs – and smaller towns and cities which lack economic scale, diversity, and in some cases connectivity, and we are seeing widening inequalities within cities. Even within successful cities there are widespread and long-standing issues of deprivation. Poverty is no longer an issue synonymous with unemployment; it is now an issue affecting many working people. We have seen a rise in low paid jobs – for example there are 80,000 jobs in Leeds which pay less than the “Real Living Wage” (the level recommended by the Living Wage Foundation). Many of these roles are insecure, part-time with limited prospects of career progression.

We are seeing polarisation of the labour market with increases in low-paid, low-skilled occupations, increases in highly skilled professional roles, but jobs in intermediate level occupations not increasing to the same extent, and in some cases declining. The rungs on the ladder of career progression are moving further apart, or in some cases are being taken away all together.

Human Capital

Cities no longer gain competitive advantage from their location relative to natural resources. Their economic success depends on the skills, creativity and innovation of their workforce and institutions.

This means education and skills need to be central to any city economic strategy. This is particularly the case in the north of England, where even at nursery age educational attainment for our young people already lags behind their counterparts in London. That north-south divide in educational attainment, school performance and skill levels is repeated at every age and qualification level, and the gap is greater for people from deprived backgrounds. It is entirely right that city leaders in the North and the Northern Powerhouse Partnership are setting out proposals to improve schools and get our young people ready for the world of work.

Cities also need to focus on attracting and retaining a skilled workforce. In the 19th and for much of the 20th centuries the workforce followed the corporation; in the 21st century knowledge economy the corporation follows the skilled and creative workforce. This means a city’s quality of life, its cultural offer, and having housing supply of the right quantity, quality, and range become must-have features, not nice-to-haves, for economic growth.

Agglomeration and Connectivity

It also means successful cities need good connectivity. The transport network enables firms to access a skilled workforce, markets and knowledge producers, and it enables people to access jobs.

Some commentators have argued that the problem with second tier cities in the UK is that they are too small; they lack the scale and critical mass to be competitive on the global stage. I think there is some merit in that argument, but I also think that the main problem is not that are cities are not too small, they are not well-connected enough. Leeds to Manchester is the same distance as London’s Central line, but less than 1% of the population of either city commute to the other one. As my colleague Dave Newton has said, better rail links between the cities of the north and the midlands through HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail will mean that when people need to move job, they do not need to move house. It will create more powerful, resilient and coherent non-London economic zones.

Technological change

Our cities are seeing huge technological change. Rashik Parmar of IBM, and a Board Member of Leeds City Region LEP, has written about these trends. They include:

- Codified services – where what is done by people is replaced by software, and what is done from traditional bricks and mortar properties in cities (such as high street retail) is done online.

- Digitised assets and pattern augmentation – enabled by the use of sensors which generate real-time data (the internet of things). This is what enable Rolls Royce to sell “power by the hour” and is creating new insights on and ways of managing urban services.

- From data to value – the huge explosion in data (over 90% of the world’s data has been created in the last two years) which is creating new insights, better public services (for example more targeted healthcare – precision medicine – enabled by health informatics), new economic opportunities, but is also concentrating economic power in the hands of the firms with access to the most data.

- Distributed ledgers, or blockchain which has the potential to be a powerful general purpose technology with positive benefits far beyond Bitcoin.

- Automation & AI which will affect financial and professional services as well as manufacturing.

- 5G, which will create new low-latency, high bandwidth telecoms infrastructure which could underpin systems for autonomous vehicles and digital healthcare.

Resilience

Extreme weather as a result of climate change is creating economic shocks, as we experienced in Leeds as a result of the flooding from Storm Eva at Christmas 2015. We need to design and build our cities to adapt to a changing climate, ensuring green and blue infrastructure is not seen as the poor relation to traditional physical infrastructure.

In the context of volatility in energy prices (something we are seeing currently as a result of extreme cold weather), local renewable and distributed energy systems have a role to play in providing dependable local supply and tackling fuel poverty.

Cities also need to ensure that their leadership and institutions can respond well to man-made shocks. Witness the exceptional civic leadership in Manchester following the Arena bombing.

Health and well-being

In an ageing society, health and well-being is a huge agenda for cities. People are living longer, but often increased longevity goes hand-in-hand with increases in serious long-term health conditions. As Leeds is demonstrating through the work of its Health and Well-being Board, and the Leeds Academic Health Partnership, it is at city and city region level where we can best integrate health and social care, and take action to tackle health inequalities.

Government and City Leadership

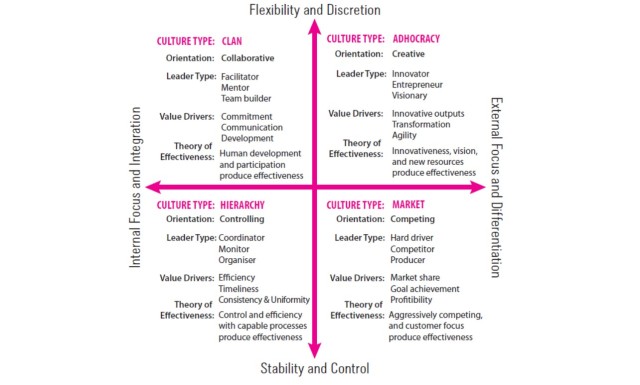

As the New Local Government Network have argued in their recent report, Culture Shock, city governments have been for some time moving away from traditional models of top-down control. In an era of austerity there is a danger of a “Market” culture taking route focused on aggressive competition, profitability, and a narrow focus on achieving goals. This runs the risk of Councils hitting their targets but missing the point of the wider economic and social outcomes they are seeking to achieve. Instead, NLGN argue for a more collaborative, clan-based approach whereby Council’s set out clear visions for change, and build coalitions and capacity across different institutions to deliver such change. This is very much in line with the concept of Civic Enterprise which Leeds helped develop through the Commission on the Future of Local Government.

Models of City Government (from NLGN Cutlure Shock report)

The City of the Future

Whilst many of these trends create threats and uncertainties, they also provide exciting opportunities. I believe cities need focus on how they, their people, places, communities, firms and institutions, can adapt and become resilient to these changes, whilst grasping the opportunities. In particular they should seek to:

- Building diverse, resilient economies, focusing on long-term productivity growth (not short-term job creation), innovation and interconnected industries, and creating places and new city districts that are attractive to innovators and entrepeneurs (creating the science parks of the 21st century);

- Generating more inclusive growth, seeking to tackle poverty (including low pay) and improve social mobility through a new model of economic growth;

- Connectivity to better link people to jobs, firms to markets, and employers to their workforce, supporting higher densities of jobs and homes, and by shaping the new future of urban mobility;

- Growing human capital by improving education, attracting and retaining a skilled workforce, putting children at the heart of city growth strategies, and making the workforce of today and the future more resilient to technological change;

- Embracing technological change, using data and digital infrastructure and services to innovate in public service delivery, and developing the concept of the city as a platform for technological innovation, based on common standards, open systems and open data (in contrast to technology provider-led models of the past);

- Tackling health inequalities, integrating health and social care, using data to join up and provide new insights to healthcare (for example, the Leeds Care Record) and using social innovation (such as the Neighbourhood Networks in Leeds) to tackle isolation and loneliness.

- Increasing resilience, by tackling climate change, improving energy security by embracing renewable and distributed energy, protecting our cities from the effects of extreme weather, and by ensuring city institutions and leadership can respond effectively to natural and man-made shocks.

- Developing new models of city governance, which are collaborative and creative and enterprising, where elected city leaders, Councils and Combined Authorities are empowered through devolution and have a positive impact disproportionate to their size through their ability to work with and through others, mobilising the organisations across the public, private and community sectors which collectively have the power to make a real difference.

Conclusion

If we are going to grasp these opportunities, and withstand the threats we need to move to a new definition of smart cities, where we are at the forefront of economic change, where we back innovators and entrepreneurs, we tackle inequality, we create the spaces for innovation and productive growth, not just those for consumption. Where we invest in human capital, particularly in our children, and in making our workforce resilient. Where digital and data is mainstreamed in everything we do – we need to be digital by default. Where we are better connected and have a transport system which supports density and places for people not just for cars. Where we shake off the legacy of the Motorway City of the 70s and become the railway and mass transit city, and the city for walking and cycling for 2020s and 2030s. Where we can help solve the challenge of health, social care, well-being and the crises of loneliness and air quality. Where our city is resilient to the impacts of climate change, and plays it part in tackling it. And we need new forms of governance that are agile, collaborative and creative.

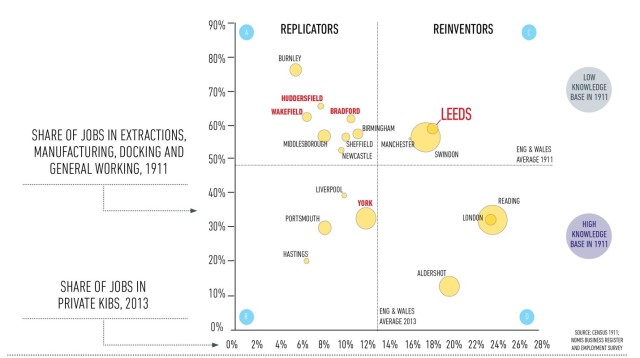

The Leeds economy has in the past reinvented itself successfully. No other UK city has made such a large shift from a production based economy at the start of the 20th century to a knowledge economy at the start of the 21st century.

Leeds: A century of Economic Change (diagram by Leeds City Region, adapted from analysis by Centre for Cities)

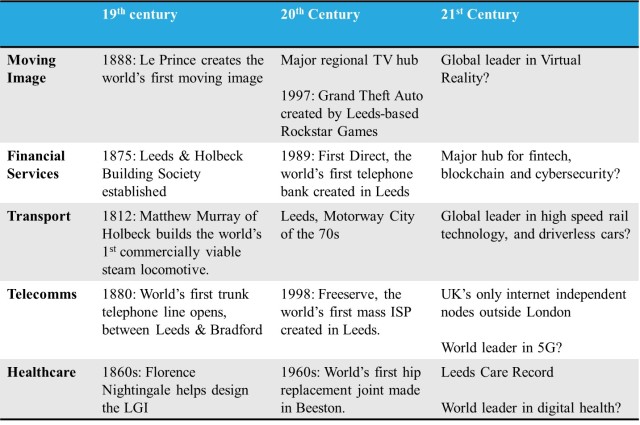

The wheel of economic change is now turning again. The foundations of our recent economic success, financial and professional services, are being disrupted by digital change. Automation will replace what people do currently. But new opportunities and new industries are developing.

Leeds: a city of innovation (diagram by Tom Bridges)

Leeds has many attributes and a great capacity for innovation. But the competition is not standing still, and the pace of change is not slowing. I believe that it is only by replicating the boldness and foresight of our city leaders, reformers and entrepreneurs in the 19th century that we will succeed in the middle and later parts of the 21st century.